A product has been added to the basket

War Poetry: Pen Heaven Visits the Imperial War Museum

War Poetry: Pen Heaven Visits the Imperial War Museum

Graves, Sassoon, and Rosenberg: three men who helped shape the way we view the First World War today. Their work has come into renewed focus this November, as a flurry of activity takes place to mark the World War I centenary. One such event is the publication by the Imperial War Museum of a new anthology of war poetry, Poems from the Front, compiled in light of the wealth of poets’ drafts and manuscripts in the museum’s archives.

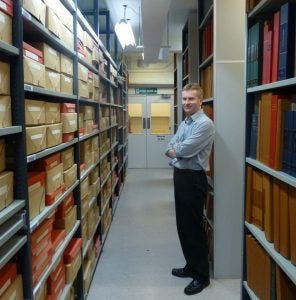

This got Pen Heaven thinking: what secrets can these drafts reveal? What can be gleaned from these muddied, yellowing scraps of paper that we can’t find in a final version, neatly typed, printed and bound for sale? To find out, we got in touch with IWM’s very own Anthony Richards. He joined the museum as a history graduate more than 20 years ago, and for the last four years has been Head of Documents and Sound. He’s a specialist in First World War manuscripts, and has the enviable responsibility of curating an archive of more than 20,000 individuals’ letters, notes, sketches and drafts.

This got Pen Heaven thinking: what secrets can these drafts reveal? What can be gleaned from these muddied, yellowing scraps of paper that we can’t find in a final version, neatly typed, printed and bound for sale? To find out, we got in touch with IWM’s very own Anthony Richards. He joined the museum as a history graduate more than 20 years ago, and for the last four years has been Head of Documents and Sound. He’s a specialist in First World War manuscripts, and has the enviable responsibility of curating an archive of more than 20,000 individuals’ letters, notes, sketches and drafts.

“It’s a great job”, says Anthony, “a bit like working in a toy shop, surrounded by lots of things that you really want to stop and read and spend time with.”

Needless to say, when Anthony invited us to come and spend a little time with some of the most precious papers in the collection, we leapt at the chance. When we arrived, Anthony showed us to a meeting room where, atop a desk, sat a small stack of files. Inside the files, manuscripts of some of the most powerful poetry ever written - handwritten by the poets themselves.

“The General”

by Siegfried Sassoon

first published 1918

in Counter Attack & Other Poems

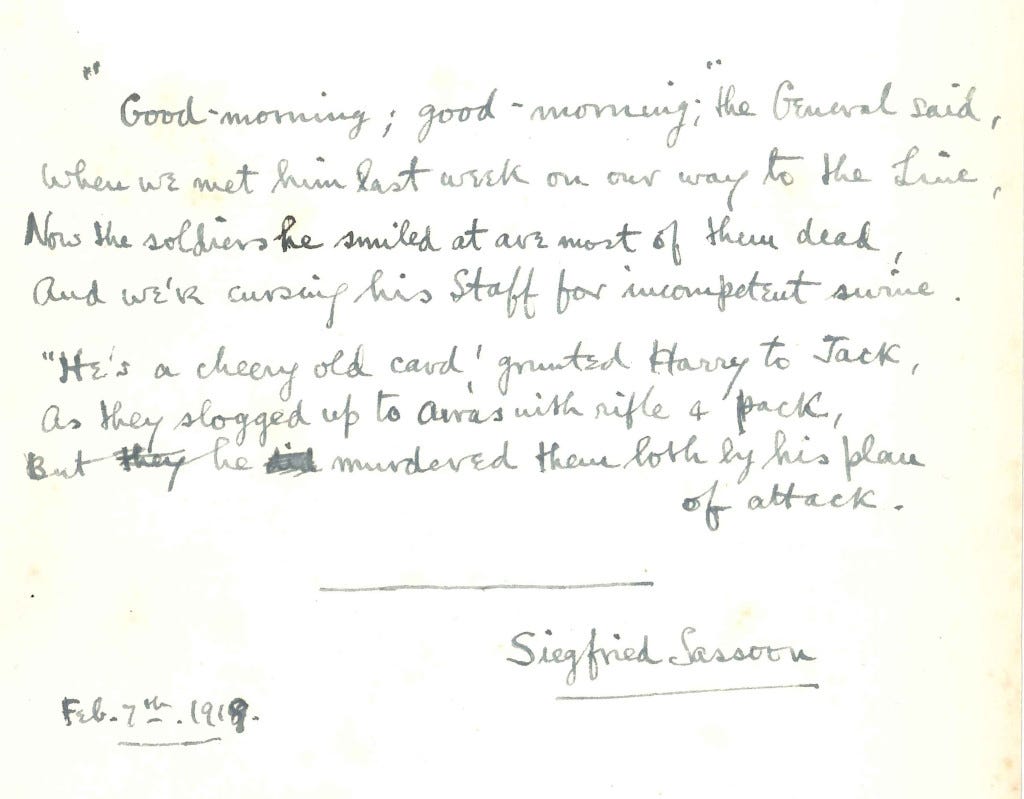

Anthony: Let’s start with this one – “The General” by Siegfried Sassoon. This is a handwritten, signed version dated 7th Feb 1919 - so written very shortly after the poem was published. What's interesting is that he's had a bit of a rethink and changed the final line. The original says, "but he [the staff officer] did for them both by his plan of attack", whereas here he's put, "but he murdered them both by his plan of attack.”

Pen Heaven: Now that’s interesting, because the published version is more typical of Sassoon in that it’s more controlled, whereas the word “murdered” feels like an outpouring of passion.

Anthony: Yes, it’s as if he thought, “no, I’m going to just go for it.” We have examples like this by a lot of poets, where they’ve written out the poem as a gift for a friend, perhaps, or even for their own pleasure. We actually bought this at auction a couple of years ago so we don’t know who originally owned, it so it’s difficult to say.

Pen Heaven: So did it have to be authenticated?

Anthony:Yeah, the auction house authenticates them and then we do a certain amount of authentication as well. But Sassoon’s handwriting is very distinctive, you could spot it straight away and there’s no reason not to think it’s the real thing.

“A Dead Boche”

by Robert Graves

first published 1917

in Fairies & Fusiliers

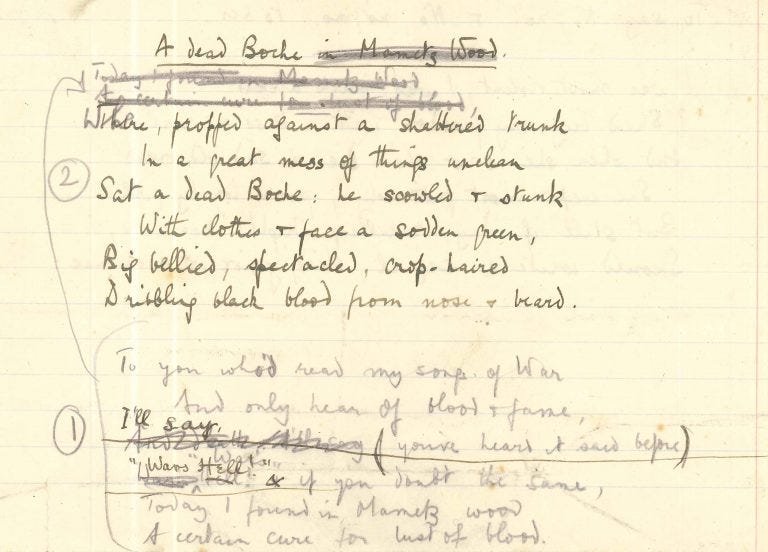

Anthony: So this draft of “A Dead Boche” is a nice example where the manuscript shows amendments by someone else. At the time, Graves was serving with Sassoon in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, so they would have been seeing each other every day – and Sassoon has changed bits. For instance, underneath this scribble you can read, “And death, I’ll say….” But Sassoon’s removed, “And death” leaving the line, “I’ll say (you’ve heard it said before)…” But also look, the first stanza was originally the second one – the poem started out the other way around.

Pen Heaven: So this draft with Sassoon’s amendments - this was the version that got published wasn’t it?

Anthony: Yes, more or less - and if you’d only read the published version you’d never have known Sassoon had had any involvement at all. Now these drafts, I always like these because they’ve got muddy fingerprints on them. He was working on these when out in the trenches hence the rough paper and the condition they’re in.

Pen Heaven: It's surprising they’ve survived so well.

Anthony:Yeah it’s amazing really.

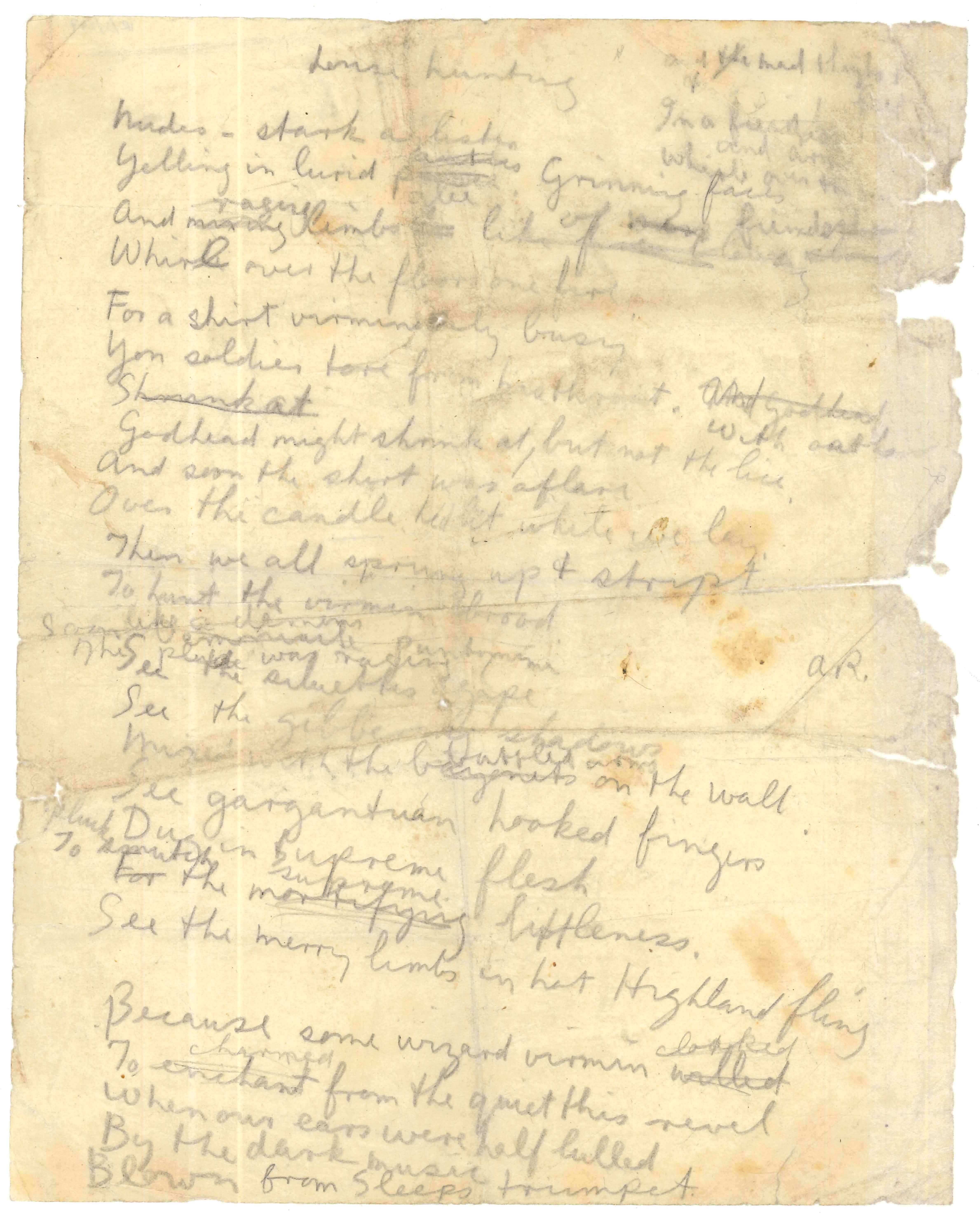

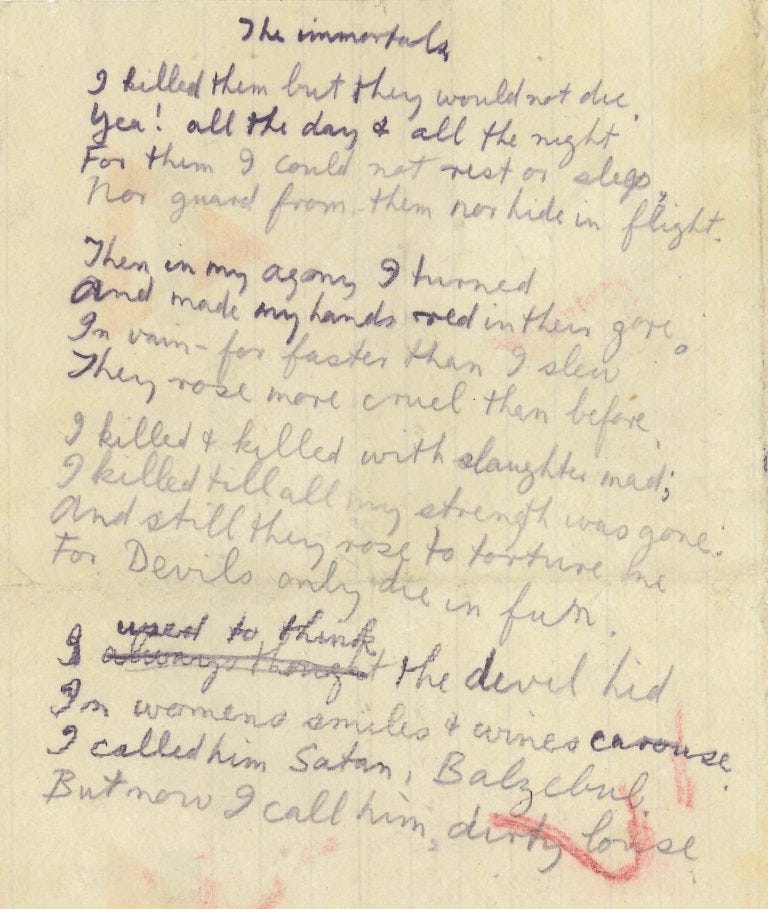

“Louse Hunting” & “The Immortals”

by Isaac Rosenberg

first published posthumously 1922

Anthony: Now of all the poets, we’ve got the most on Rosenberg. The collection is enormous, and one of the reasons there’s so much is the way he wrote.

He was always trying to get his poems published, so he would send them home where one of his relatives would type them up and then send them back. So you often get typed versions with signatures, some that he’s received and then fiddled with. So there’s loads of different versions of the same poem.

But unlike Sassoon and Graves, he wasn’t an officer, so he was pretty penniless and had to use any old bits of paper he could find. The collection is made up of all sorts of different little scraps, and a lot of the poems are written on the backs of rough notes or letters. Some of them are in a terrible condition.

|

|

|

Pen Heaven:That’s fascinating - that you can see a soldier’s class in the things that they’re writing on. And can we know for sure that this damage happened while they were his possession?

Anthony: Yes, because all of this we acquired direct from the family, so something like this could have been with him when he was killed, or more likely was sent back to his family.

Pen Heaven: And he seems to prefer pencil?

Anthony: Yes, that’s quite common. It reflects the fact that if you were an officer in the trenches, you may have had a pen and inkpot in your dugout, but normal private soldiers would have had just a pencil and a knife to sharpen it. Or occasionally, as with “The Immortals” you get something in this slightly purple crayon. It was used to use to censor letters by scribbling out the names of locations, but it was also often used for personal letters. Now, “The Immortals” and “Louse Hunting” make an interesting pair because although they’re both distinct poems in their own right, “Louse Hunting” is actually a revision on the former, and it shows how a poem has developed. They both talk about trying to get fleas out of the seams in your clothes, which was a constant struggle for soldiers in the trenches, but whereas “Louse Hunting” makes it obvious, with “The Immortals”, you kind of have to know where he’s coming from.

Pen Heaven: “The Immortals” isn’t quite as good a poem is it.

Anthony: No, probably not. But Louse Hunting, you can see, has been carried around in his pocket for a while, and any spare moment he was going over it in his mind. You can trace the edits on the page, and see how he was and thinking, “smutch” is better than “pluck” and “supreme” is better than “mortifying,” “charmed” better than “enchant”.

If you go back to a draft like this, you can follow his train of thought.

~~~

Before we left, Pen Heaven asked Anthony one final question. “Do you have a favourite war poet?”

Anthony: “Sassoon, I think. People often don’t realise it, but he was the most influential, and helped to publicise a lot of the others. Wilfred Owen is often the one that people single out as the best of the War poets, but without Sassoon, Owen would have been completely overlooked.”

In a sense, it’s that aspect of Sassoon’s work that Anthony and the Imperial War Museum continue to this day. With the poets and their last surviving comrades now all gone, the closest thing we have to living memory of World War I is the art that they left behind. From these filthy scraps of paper - with their faded ink, smudged pencil and fingerprints made with the mud of Flanders’ fields - echo the personal stories of the men who documented human history in its darkest hour. Stories that would otherwise be lost to the sands of time.

Afterword

The final drafts of these poems are all included in IWM’s anthology Poems from the Front, along with the works Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke and more of the Great War Poets. IWM Press Office Assistant Kate Crowther talked us through the new edition. “Poems from the Front is the first anthology to have been compiled with the wisdom that’s in the IWM collection. It was edited by Professor Paul O’Prey, a trustee of the Friends of IWM and also a close friend of Robert Graves. The biographies inside are packed with knowledge from research that he undertook here, and the book brings a new perspective on the poetry’s historical value, showing how dynamic, daring and volatile it was for the time.” If you’d like to purchase Poems from the Front or to view any of the other materials in the IWM online store, click here.

The final drafts of these poems are all included in IWM’s anthology Poems from the Front, along with the works Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke and more of the Great War Poets. IWM Press Office Assistant Kate Crowther talked us through the new edition. “Poems from the Front is the first anthology to have been compiled with the wisdom that’s in the IWM collection. It was edited by Professor Paul O’Prey, a trustee of the Friends of IWM and also a close friend of Robert Graves. The biographies inside are packed with knowledge from research that he undertook here, and the book brings a new perspective on the poetry’s historical value, showing how dynamic, daring and volatile it was for the time.” If you’d like to purchase Poems from the Front or to view any of the other materials in the IWM online store, click here.

Please note that these scans of poets’ handwritten drafts are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holders. For permission to publish copyrighted material by these poets, please use the relevant contact details.

Siegfried Sassoon Barbara Levy Literary Agency 64 Greenhill Hampstead High Street London NW3 5TZ T: 020 7435 9046

Isaac Rosenberg Laura Jones Ben Uri: Art, Identity and Migration 108a Boundary Road St John’s Wood London NW8 0RH T: 020 7604 3991

Robert Graves Ilaria Tarasconi United Agents 12 – 26 Lexington Street London W1F 0LE T: 020 3214 0800

Comments

What an incredible opportunity! I love the Imperial War Museum, probably one of the best museums in the world.

Thanks for your comment - you're right, it was a great opportunity and we really enjoyed our visit. Did you know the whole IWM collection is public? If you like, you can make an appointment to see things that aren't normally on public display.

Thanks for your comment - you're right, it was a great opportunity and we really enjoyed our visit. Did you know the whole IWM collection is public? If you like, you can make an appointment to see things that aren't normally on public display.

What an incredible opportunity! I love the Imperial War Museum, probably one of the best museums in the world.